You Are Inventory

Yesterday I read a newsletter from another writer named Dave Karpf, in which he offered a framework for understanding the current AI bubble. His framework is comprised of the three stories he says we can tell about the dot-com bubble and subsequent crash: 1. overvalued startups and out-of-control speculation, 2. capital expenditures beyond the bounds of reason, and/or 3. massive, fancy financial fraud. In other words: 1. Pets.com, 2. Global Crossing, and 3. Enron. Each of these narratives, he says, can be applied to the madness surrounding AI. But Dave argues that, at the end of the day, the AI story will essentially be the story of Enron.

Now, I like frameworks that help us make sense of things. I like analogues that illustrate those frameworks. Framing the current AI bubble as a massive financial shell game (Enron) or as a massive Ponzi scheme (from the comments) is helpful. And yet! This framework feels incomplete, as far as analyses go. It only tells part of the story, and worse, it creates what I like to call a dead end for the reader. Sure, there's a snappy takeaway you can share with your friends and colleagues: The AI bubble is like Enron, companies trading value back and forth to make it look like there's more value! But then what? What more can you understand about how we got to this point, and what more can you understand about what we might be able to do to get ourselves out?

You might argue that we don't need to do anything else besides see it in one of these three narrative lights. In fact, you might argue that we can't do anything else. These are massive financial and institutional forces at work, far bigger and more powerful than all the rest of us put together. So the best we can hope for is to sound smart at the bar, when we all meet up to watch the world burn as ever more AI slop is churned out.

I would argue these narratives are part of why we can't do anything else. Yes, hubris. Yes, capitalism. Yes, greed. But I think there's more to the story.

One of the things you learn as a user researcher in tech is that people reach for analogues as a form of shorthand. This is easiest to understand when you're working on a product, trying to solve a user need or testing out a new feature. People – end users – will explain to you what it is they want to do in large part by explaining what feature they think they need. But starting with a solution is rarely, if ever, the way to build the solution. The feature a user thinks she needs or the solution he posits to a problem he may not fully understand is essentially a proxy, a rough approximation of what seems like it will work. It seems good enough to get the job done. So each time we reinforce the three narrative shortcuts that supposedly explain the dot-com bubble, we keep ourselves from getting the fuller understanding of the truly big picture, and to the deeper roots of the problem.

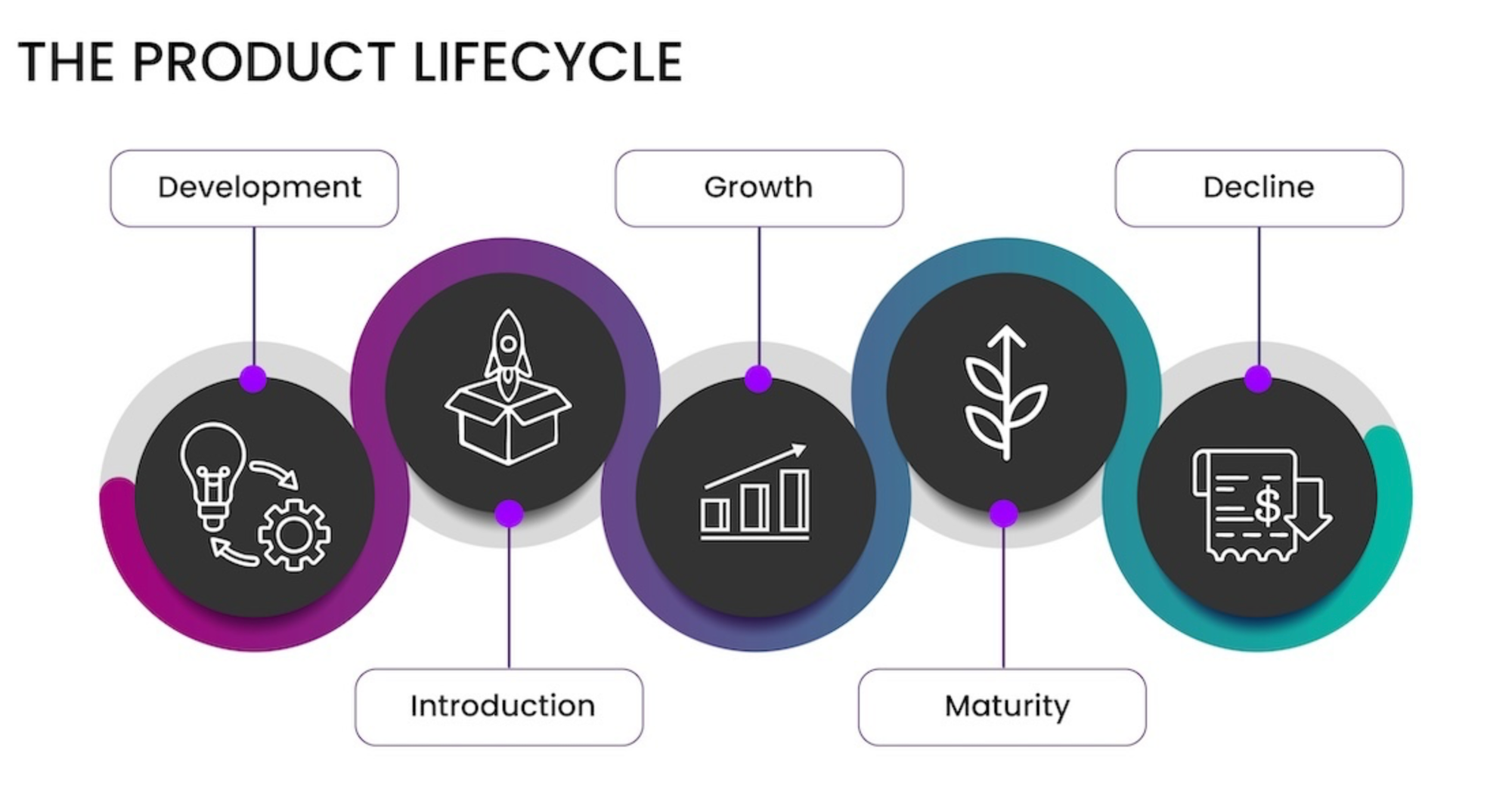

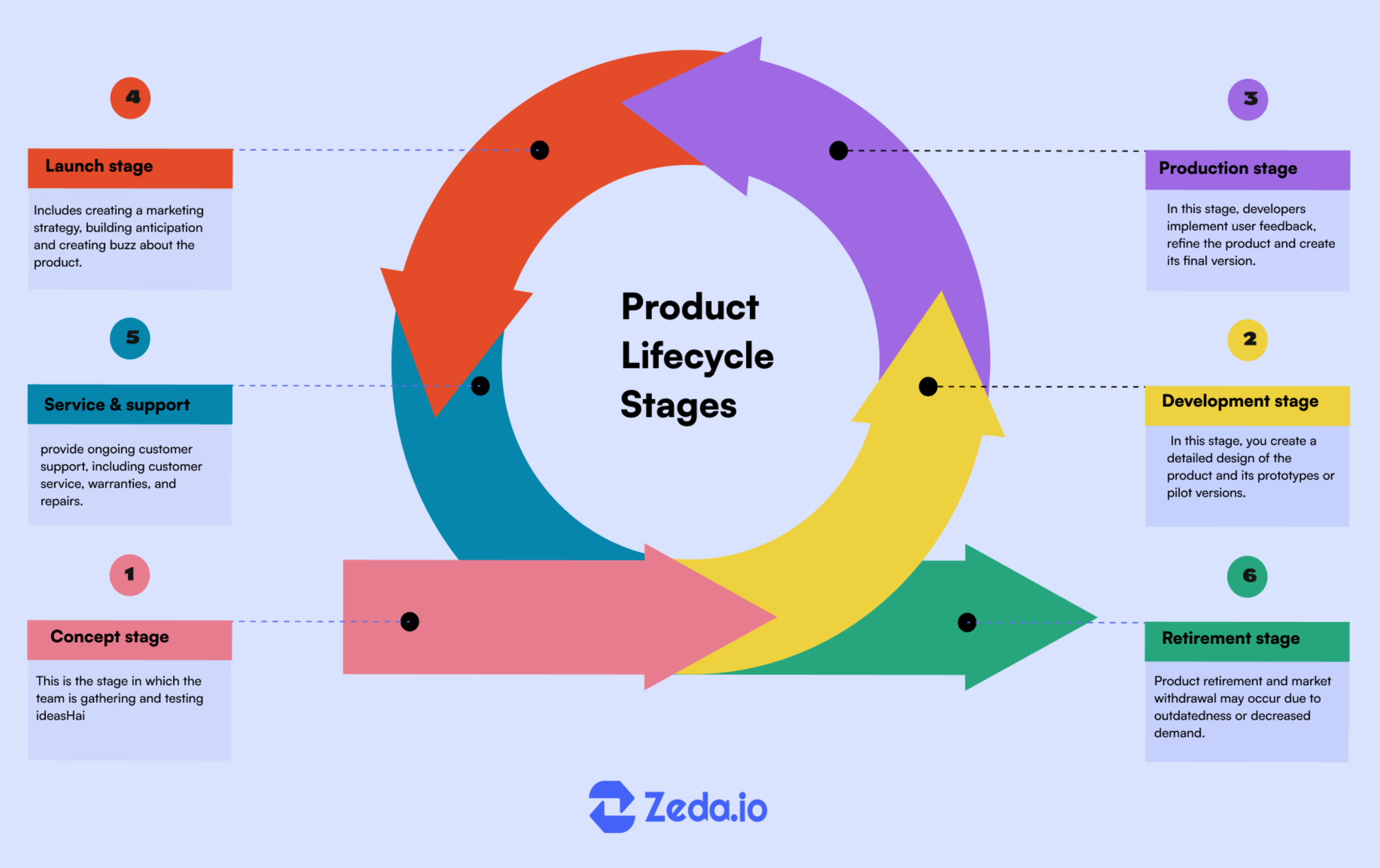

In product development, a tech product lifecycle goes something like this: concept, development, introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. Each one of these stages can be broken down further, especially early on. There's a lot of ideation and iteration, a lot of trying to land on the thing that works, build confidence, test it, tinker more, and so on. Here are two diagrams I stole from some other websites. Hopefully no one gets mad at me for this.

I like to think of the dot-com bubble not as a discrete phase of the tech industry but rather as the industry's first public beta test. The industry didn't begin in the dot-com years and it didn't end when Nasdaq both peaked and tanked in 2000. Sure, the dot-com era had its many absurdities and failures, but it was also a time during which a lot of important infrastructure was created, a lot of ideas were stress tested, a lot of innovators and early adopters showed up to try things out, and a lot of lessons were learned. The infrastructure was more than fiberoptic, and the lessons were more than financial.

In fact, one of the lessons was about the value of infrastructure. Companies that not only survived the dot-com era but thrived: Google, Amazon, Apple. Companies that emerged in the aftermath of the dot-com era: Facebook, Twitter, Netflix. These companies, among others, comprise some of the most important and inescapable infrastructure of all our lives, so much so that they have eroded and in many cases replaced preexisting, longstanding forms of infrastructure. Social and community infrastructure, entertainment infrastructure, commercial infrastructure, information and communication infrastructure. To control infrastructure is to control nearly everything.

Another big lesson came in the form of redefining what constitutes inventory. When I was at Instagram and my team was creating the earliest version of what would become the Notes feature – the little messages friends can post at the top of your inbox, above your direct messages – we had to make a decision about the audience for this feature. The intent of the feature had been to create a sort of social cue for teenagers, a way to invite messages from friends or to know it was okay to message someone else. Think of it less as an ambient badge and more as a little flare you could send out: "Is anyone around? Does anyone want to study with me? Can someone comfort me? Who wants to play video games?"

The problem, however, was that Notes was a net-new feature for Instagram. There was nothing like it in the app, so users would be unsure of how it worked and possibly unwilling to take the chance and try it out. Introducing a feature in an app is challenging: You can't explain how it works too much, you have to make sure people can find the feature, it has to seem both intuitive and desirable to use. Most people look to others to mirror behavior. There's safety in numbers, right? Very few people will take the chance to try something out if they're not sure what it's for or how it works, because very few people want to look stupid in front of others, especially not teenagers.

If you want a feature to succeed, you need enough people to use it that a few brave early adopters will try it out and model the behavior, so much so that others will see it's safe, and then will try it out themselves. If you only show it to a small group of people, like to the people on your close friends list (which we had intended), you might not get anyone to model this behavior. So, many people internally at IG argued for the notes you post to be visible to all your mutuals, i.e. everyone who you follow and who follows you back. The way they explained this?

There needs to be enough inventory to guarantee that most people will see mutuals sharing Notes at the top of their inboxes, and thus will be more likely to try the feature out.

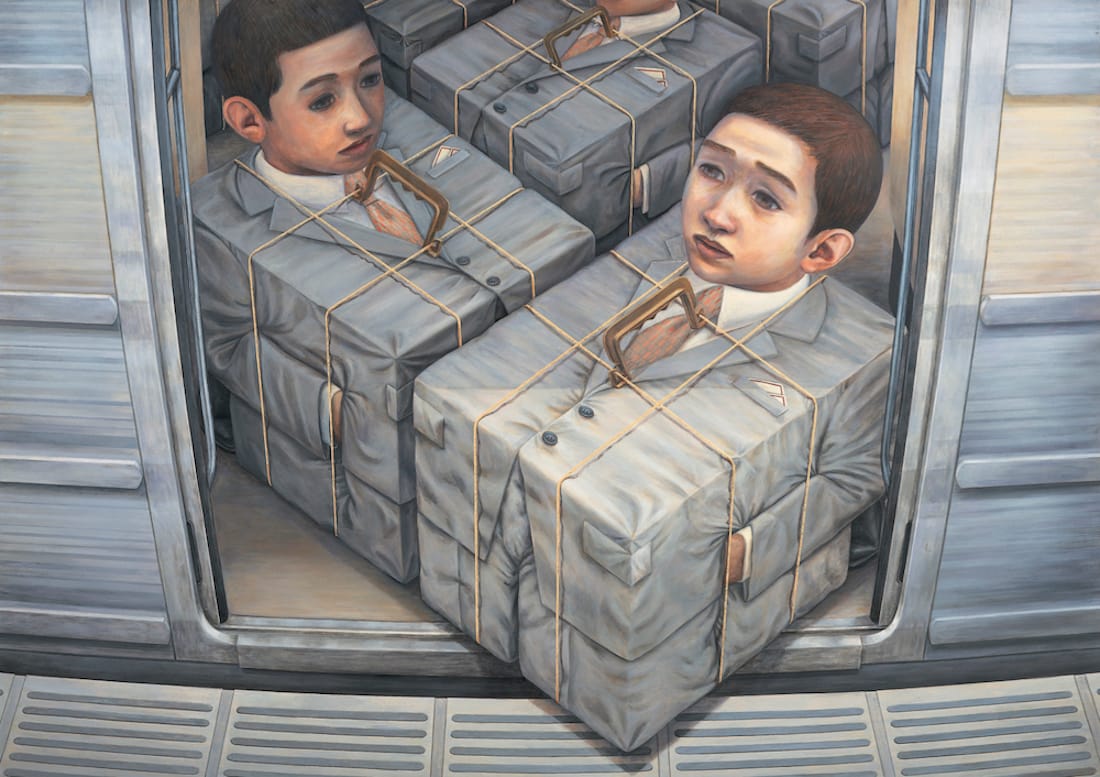

Inventory. There needs to be enough inventory. That's what your content is. That's what you are. That's what the industry discovered in those years between the dot-com bubble and the rise of the new tech giants. They learned that you are their means of production.

So when I think about the AI bubble, which certainly is a bubble, I see more than Dave's three narratives. I see more than money. I see industry players willing to do whatever it takes to control the infrastructure and to control the inventory. And if we don't start talking about that story, we'll never get out alive.

Until next Wednesday.

Lx

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.