The Big Moonshot

The year before I got hired at Instagram, I interviewed at Facebook. My interview was in the spring of 2019, two and a half years before Facebook became Meta. I didn't particularly want to work for Facebook—in fact, I didn't want to work for Facebook at all—but I was working at Spotify HQ in Stockholm, and my two years there had been professionally frustrating. Those were the halcyon days when there were actual job openings, so I was shopping around, responding to recruiters and setting up interviews. Someone I knew had started working at Facebook 0n a virtual reality team, and she loved it. I figured what the heck. Always take the call, right? Better to have the option to say no than to have no option at all.

My friend submitted my application as an internal referral for a role on the AR/VR team (augmented and virtual reality), and a recruiter reached out to me very quickly. During the process, the then-head of research at WhatsApp somehow got wind that I was looking for a new job, and she pounced. Would I be interested in working at WhatsApp as well as in AR/VR? she wanted to know. They were expanding into WhatsApp for work, and my experience at Slack made me a good fit. The interview process would be the same, so I said sure, why not.

Once I made it through the interview process and it became clear the company wanted to extend an offer, the recruiter told me that I needed to pick which team I'd want to work with in order for the offer to be formalized. Did I want to work on newer augmented reality technologies, or did I want to work in the more-familiar communication space? I liked both hiring managers, and both roles interested me about the same amount. As someone who is now good at picking favorites even in extremely low stakes situations, this presented a challenge.

At one point, I mentioned this dilemma to the product manager on the AR/VR. He said, "Well, it's like this. Do you want to work on technology problems or do you want to work on human problems?" He went on to explain: AR/VR was a technology problem at that moment. The technology barely existed, relatively speaking. Entire foundational platforms needed to be built in order to figure out what would even be possible to create. Once that was done, then it would be time for figuring out what people problems to solve, for asking the human questions.

This, he told me, was the kind of work that excited him most. He wanted to build the next world, the new paradigm. The modern internet had been built long before his time. The foundational building blocks, the languages and platforms already existed. Very little was conceptual or truly visionary, and in that world, all he could do was make stuff within the constraints of a world he didn't get to shape. The WhatsApp work, on the other hand, was not at all a technology problem. At 10 years old, WhatsApp was a mature product, at least as far as apps go. What's more, it was a messaging tool, and there's only so much you can do with texting, chatting, messaging. That role, he said, would be about incremental changes, about finding use cases for something that had already been invented, about how this extant product fit into an extant universe. But it would also be about helping people find solutions to real needs and problems in their lives, and he said, based on what I'd told him, that seemed like the thing I was more interested in.

In the end, I didn't go to work at Facebook on either team. But I still think about this conversation all the time, in part because it was the moment I realized what an absolute idiot I had been. Why did I ever think I could convince companies to care about human beings? It's literally called the tech industry.

Don't get me wrong: I know it takes all kinds of people to make products. We truly need people to be passionate about the tech part of it. The framing this PM gave me made total sense, and I truly appreciated and admired it. It was a great way to look at the decision I had to make as well as the bigger picture, the work of building products and creating solutions. What clicked in my head was the clear order of operations: Tech first, humans second. Is it possible to reverse that?

Last week, after I shared my newsletter on Bluesky, I had a brief but very helpful exchange with Ian Bogost who mentioned a tech-specific obstacle to the kinds of infrastructure changes I was suggesting last week. That, plus a lovely comment on the post itself, made me want to clarify something, for myself as much as for anyone else:

I don't have the technological answers. I don't yet know what specific solutions or innovations we need to make this better. We can't come up with the answers until we start asking different—better—questions. Not just of the tech itself, or the industry, or the new entities that might be able to do this work, but of ourselves as individuals and as a society. Can we redirect our anger, muzzle our egos, and channel our energy? Will we step out of these performative spaces and figure out how to reconnect with each other? Is it time for us to stop looking to technology to do the work for us, and instead do the work ourselves, facilitated by these tools? Are we willing to put humans first, and technology second?

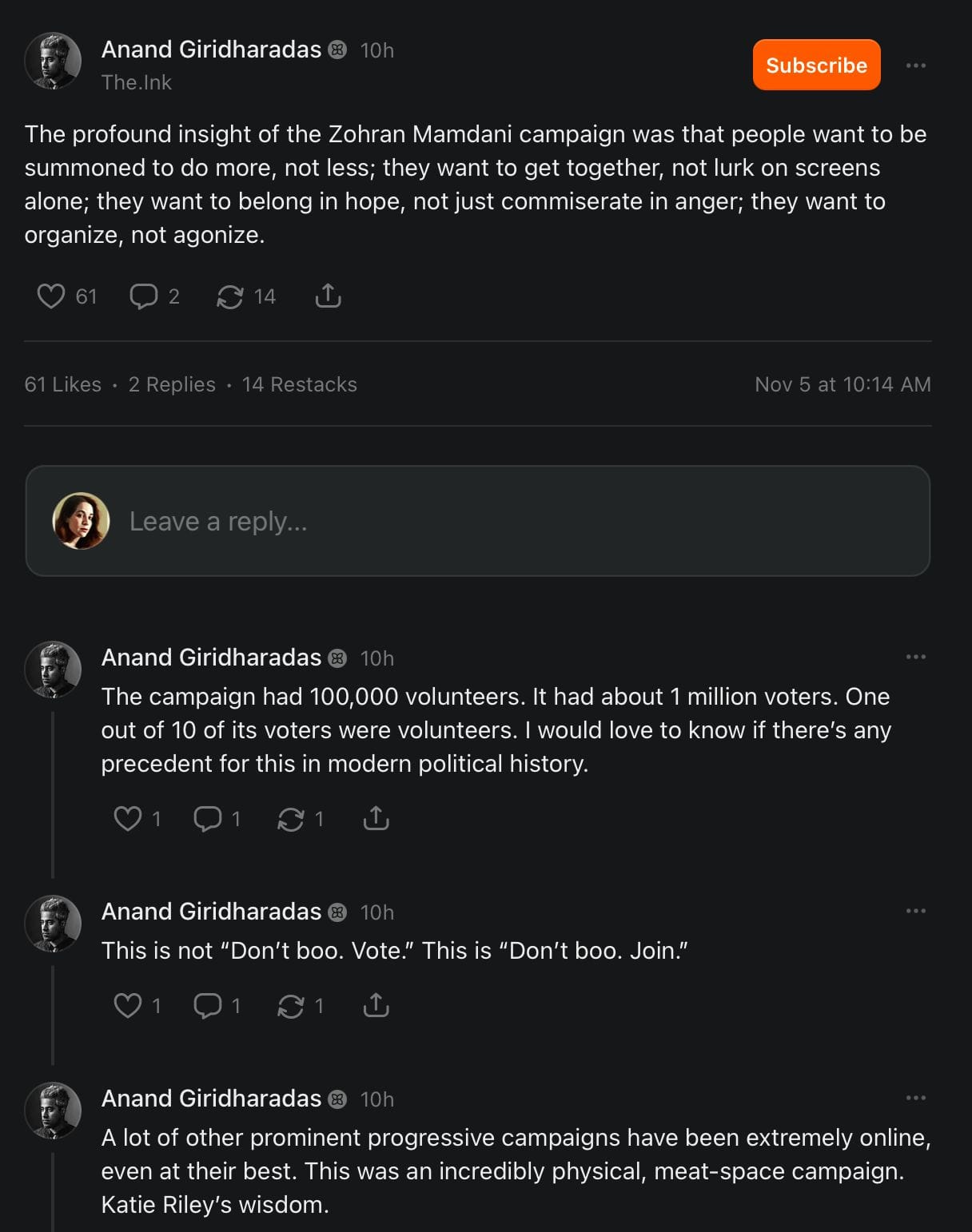

When I put it this way, it sounds so pie-in-the-sky that I wonder if I'm being corny or naive, if this is an unattainable idealism. But you know what? Fuck it. We're all thinking a lot about the NYC mayoral election, right. Set aside Mayor-elect Mamdani for a moment (as well as any feelings you may have about him), and instead look at the campaign that took him from polling at 1% to winning the election. Here's something I ran across on Substack (sorry).

It's funny to use this "the campaign was physical, in person, meat-space oriented" analysis here when I'm talking about our digital lives. But all of this is actually a useful analog. The campaign wasn't simply about the in-person-ness of it all, it was also real human connection. Community and coalition building, one-on-one conversations and sharing, and the many, many hyperlocal experiences of communities across the city—all of which connect to a more universally shared experience. You've seen me talk about this before in the context of creating better technology: The connection of the individual to the universal, and how powerful that is. One thing the campaign recognized was that we engage with our environments on so many levels. We are individuals worried about paying rent, but we're also part of ethnic and religious groups. We exist in our neighborhoods, but we also exist in the larger city. There is no one New York City, but there also is only one New York City.

This is the sort of shift I am after when it comes to technology and the internet. We have to treat our digital spaces the way we treat our physical cities and our civic worlds. Yes, the infrastructure issue is a hard one to solve. Yes, we are more divided and disillusioned than we have been in a long, long time. We have a million bad habits to change, including a crippling dependency on convenience and immediacy. But I dunno. Why not give it a shot? I'm looking for the tipping point. Will it be convincing 3.5% of you tech people to build it? Getting 10% of you non-tech people to make the effort to do what you can as well? Who knows. I'll just keep asking this until we get there:

What if we could break away from the institutions and infrastructures that have us in a stranglehold, and build a New Paradigm?

Until next Wednesday.

Lx

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.