That's What the Humans are For

When I joined Instagram in the summer of 2020, I hoped it would be my last job in the tech industry as a user researcher. Not because it was my dream job. Even though I was pleased to have gotten the role and was excited about the work I'd be doing, I had long sensed I was approaching my own expiration date of user research as a profession. Instagram was the third big-deal sexy tech product I was going to work on, having previously worked at Spotify and, before that, at Slack as that company's first user researcher. Each product was different, with different users and different considerations, so the work itself was never exactly the same. But the overall shape of the work, the rhythms, processes, and conversations? Pretty similar. Similar enough, at least, that I already knew what corporate obstacles would trip me up, which parts of the performance review matrix would give me the most trouble, and approximately how long I'd last before asking the inevitable too-spicy question or saying something in a meeting to the product lead who thought his product sensibilities were a special and unique form of genius that was always better than my insights.

Unlike many of my coworkers, I never much wanted to transition into management or run a research department. I wanted to lead and make decisions, but I didn't want to spend my time in meetings, doing paperwork, or pretending to be super excited about new company initiatives. When Facebook became Meta, I knew I would never be able get up in front of people and say, with a straight face, that I was excited about Meta's new catchphrase, "Meta, Metamates, Me." Plus, I was always in tech but not of tech. Tech was where I was both an insider and an outsider, and I always felt that acutely.

I also didn't want to keep doing the routine pieces of user research. Somewhere along the way, I'd figured out that my skillset and approach to research were, if not unique, then pretty different and rare in the industry. I mixed together user research, strategy, product thinking, and more to come up with new frameworks that shifted people's perspectives and allowed them to move in new and better directions. I strongly believed that a fundamental aspect of my role was to bridge the divide between the people who used products and the people who build products by developing a more natural language of insights, one that allowed builders to advocate for users without even realizing they were doing it. I also believed that a central aspect of my role was to advocate, whether for the good of the end user or for the good of my colleagues, even if that came at the expense of my own career. I cared about the human side of things, in an industry that fundamentally didn't.

With each job I felt a growing disconnect between what companies thought they needed from a user researcher and what I knew I was best at. Plus, even if I hadn't been approaching my own inner expiration date, there was another I had my eye on. How many women over 50 do you know who work in tech, and in particular who work as independent contributors? So I saw myself working at Instagram for at least five years, maybe even more, until I figured out how to create or find my next path.

And then 2022 happened. As you may remember, in November of that year Meta had mass layoffs for the first time in its corporate history. A staggering 13% of the company would be let go, which meant 11,000 jobs. Corporate leadership was of course unable to promise there would be no further cuts, but they did say they made such significant cuts in order to avoid additional rounds of layoffs. And then, I guess after remembering how much the stock market enjoys a hearty human sacrifice, they went ahead and did another three rounds in March, April, and May 2023.

In the tech industry, when one of the FAANG (now MAANG) companies does something, it inevitably starts some sort of domino effect. (F/MAANG = Facebook/Meta, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google.) True to form, other companies across the industry began slashing roles and laying people off. There were all sorts of reasons companies started doing this beyond the domino effect, such as increasing interest rates and changes to research & experimentation tax credits. These shifts meant companies would be unable to borrow money essentially for free to hire and pay salaries and benefits, and would instead have to use their own capital. I mean, can you imagine? So awful for them. Better to ruin a lot of lives instead.

All told, approximately 21,000 Meta employees were let go in 2022 and 2023, with thousands more from other companies. Surprisingly, this included software engineers, heretofore the most cosseted and treasured employees of the industry. In fact, when anyone would talk about how hard other roles were hit, someone would inevitably trot out, "The same number of SWEs were laid off as user researchers!" Yes but: In any data set, absolute numbers tell only one small piece of the story. There are far, far more engineers in the tech than user researchers. So if the numbers were the same, then that meant the user research discipline had been decimated across the industry. Teams were gutted, and the market was flooded with job seekers. But, of course, there were no jobs. And I mean NO jobs. Someone crunched the numbers and found that, in January 2024, user research job listings were down 89% from their peak in 2022. I don't know what the current numbers look like but I'm pretty sure of two things: research teams and available roles are nowhere near what they were in 2022 and they will likely never recover.

Which meant that Instagram really was (almost*) my last tech job as a user researcher. Be careful what you wish for, I guess.

I know I've written about all this before – more than once, in fact. This entire topic is the reason I started this newsletter to begin with! But I like revisiting it for many reasons, least of which is that most writing about this is very niche and focuses on the nuts and bolts of user research for researchers, or at least for people in the industry. But you should know and care about it too. The tech industry claims to want super smart people thinking outside the box to solve the most important problems. And yet, when it comes to the actual human part of those problems, the industry doesn't want that outside the box thinking, those smart people who will push back. It wants worker bees who cheerfully do the work and don't rock the boat. Enter AI.

Why should this be important to you? Well, think about it this way: How many people who work in tech and make the products you use are tasked with representing your interests? Not the company's interests. Not the engineering team's interests, when they don't want to be saddled with tech debt or forced to make decisions that will complicate whatever cool thing they're working on. Not some employee's own personal interests, like their career growth or intellectual curiosity. Not the interests of whatever stupid bullshit political battle is being waged by two VPs you don't know and will never talk to.

Do you know how many considerations are taken into account when it comes to building a product or even a single feature? It's so hard – SO HARD – to get teams to prioritize what is best for the end user. And the fewer researchers there are, the more scared those researchers are to rock the boat, the less likely that prioritization will happen. So if you didn't like the direction products took when there were user researchers working on those teams, what do you think is going to happen moving forward?

Advocating for you and other users, being your voice, arguing for what will improve the product in ways that benefit you as a user, shifting perspectives and building a language that allow for better outcomes – those are things a human being can do. Or at least try to do. This is true in every field. Not just user research and product development. Yes, there are things computers can do better than humans. But there are things humans can do better than computers, things I don't know that computers will ever be able to do, at least not in my lifetime.

Earlier today I read this sunny little article in The Guardian that a friend sent to me with the description: "This is literally psychotic." The headline: OpenAI CEO tells Federal Reserve confab that entire job categories will disappear due to AI.

Here's the insane first paragraph:

During his latest trip to Washington, OpenAI’s chief executive, Sam Altman, painted a sweeping vision of an AI-dominated future in which entire job categories disappear, presidents follow ChatGPT’s recommendations and hostile nations wield artificial intelligence as a weapon of mass destruction, all while positioning his company as the indispensable architect of humanity’s technological destiny.

Wow, sounds great Sam, I can see why you would want to build this and also say all of this out loud. Sign me the fuck up!

He goes on to say that roles like customer service will be completely replaced by AI. After last week's newsletter, I had a conversation with a Bluesky pal who argued that more technology might actually be beneficial for customer service, given the amount of abuse customers will heap on humans at the other end of the telephone, chat, or email. AI assistants could help provide basic information, saving humans from having to deal with difficult customers. It's a great point. But when I hear someone in a position of power say that some roles will be "totally, totally gone," roles that are already invisible and un-celebrated and that pay much less than most other jobs, I don't think this is being done for the benefit of human beings who aren't named Sam Altman and who aren't going to get rich off more human sacrifice.

Altman even goes on to say the following, a few paragraphs later:

The OpenAI founder then turned to healthcare, making the suggestion that AI’s diagnostic capabilities had surpassed human doctors, but wouldn’t go so far as to accept the superior performer as the sole purveyor of healthcare.

“ChatGPT today, by the way, most of the time, can give you better – it’s like, a better diagnostician than most doctors in the world,” he said. “Yet people still go to doctors, and I am not, like, maybe I’m a dinosaur here, but I really do not want to, like, entrust my medical fate to ChatGPT with no human doctor in the loop.”

Let's sort of set aside the fact that GenAI often can't get basic facts right or write good computer code. Let's sort of set aside Silicon Valley's penchant for insisting everyone else should use their products while being unwilling to subject themselves and their children to those products and the harm they cause, which has been going on since at least 2018 and probably long before. What I find fascinating here is that even Sam Altman is admitting outright: There are things that require a human being, that only a human being can do. Even if the machine is right, I wouldn't trust it with my life. I would trust a human.

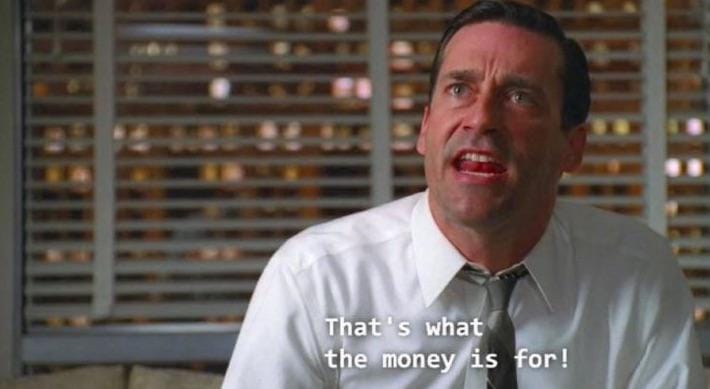

There are already lots of people out there who don't think user research is a real job or a really valuable job. This includes many of my old coworkers, and it even includes other user researchers I know. Just like most jobs, there are aspects of it that are useful and aspects that are bullshit. There are also people out there – like Sam Altman – who are ready to unleash products that wipe out millions of jobs and increase our entanglement with technologies that not even he fully trusts. User research job listings are already full of AI requirements, and researchers are using AI tools more and more, essentially training these tools to wipe out their jobs when the time is right. But again, what happens when we need to trust that someone has our best interests at heart? Who can we entrust our lives and our fates to? That's what the humans are for – but for how much longer?

Until next Wednesday.

Lx

*I did work as a contractor at Mozilla for a year and change, hence the almost. So I guess Instagram/Meta was my last big tech employer.

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.