Open Source the Revolution

Before I was a contractor at Mozilla, I'd never spent much time thinking about open source software. I knew what it was obviously, had friends who cared a lot about things like decentralized development and universal distribution and other keywords from the open source Wikipedia page. But I'd only ever worked on products with proprietary software, and I'd also spent most of my time thinking about the people problems more than the tech problems. Then I worked on Firefox for a little over a year, and since it's an open source browser, open source became something I had to pay a lot more attention to.

Now, while some of you are intimately familiar with open source as both concept and practice, that won't be true of everyone who reads this. I think I have readers who don't know what open source is, maybe haven't even heard of it. To be honest, I can't promise that anyone will understand it better after I'm done, because I am neither programmer nor software engineer, and I don't even know how to push code to a repo, let alone find the source and tell you what it means. But please bear with me for the next few paragraphs, even if this is common knowledge to most you, because I want everyone to go on this journey with us. One thing I can do is publicly embarrass myself by attempting to explain. Please enjoy.

Computers do not use the same type of language that we do. This is a fun thing to think about in general, but specifically in this present moment when companies are trying to convince you their artificial intelligence products are really speaking to you. Incorrect! Because again, fundamentally, computers and humans use different languages. In order for a human to speak computer, a human has to learn new languages, ones a computer can understand and process. And in order for a computer to speak human, it needs instructions to take what it does and translate it into something that people can read. Like if you could go into Google Translate, but instead of you trying to say "where is the bathroom" in Tagalog, the computer needs something to translate instructions written in Python into something you recognize as "please give me more private information about your life because I truly care about your wellbeing."

I started thinking about this a long time ago because of my father who, as you may recall from past newsletters, is a programmer and systems architect. My dad is not multilingual, in the human sense. He speaks English, and I think he's come to understand a little bit of Spanish. But when I tell you he is like the Tower of Babel when it comes to computers – The Code Whisperer! – I am not even joking a little bit. Over the course of his life, he's learned at least seven (7) computer languages that he can really program in, and he's dabbled in at least three more. This man visualizes code. He creates software that is clean, fast, and doesn't break, and by creates I mean yes, he's still working.

By way of comparison, I speak two, kind of three human languages. English, Spanish (fluently once upon a time, conversationally now), French (almost fluently once, god even knows now). I've known and/or learned others. I started speaking very, very early, like well before I was a year old (and I have not shut up since), and I had two first languages, English and Cantonese, thanks to a babysitter I spent a lot of time with. Cantonese is lost to me now, but when I took Mandarin lessons some years back, the teacher said I picked it up twice as fast as other students, likely because I had that little tonal language brain structure still hidden away. I've dabbled in Swedish, Italian, Portuguese, Japanese. If I spoke seven human languages you'd all think I was extraordinary! This is what I mean about my dad.

I didn't think about computer languages this way for a long time, which saddens me because I think if I had, I'd have been more interested in learning to program a long time ago. But whatever, water under the bridge. Thinking about it this way now is useful for many reasons, not least of which is what I was talking about before this digression: Open source. In order to understand open source, you have to kind of know what source code is. And in order to understand source code, you have to know that computers and people don't "naturally" speak the same language.

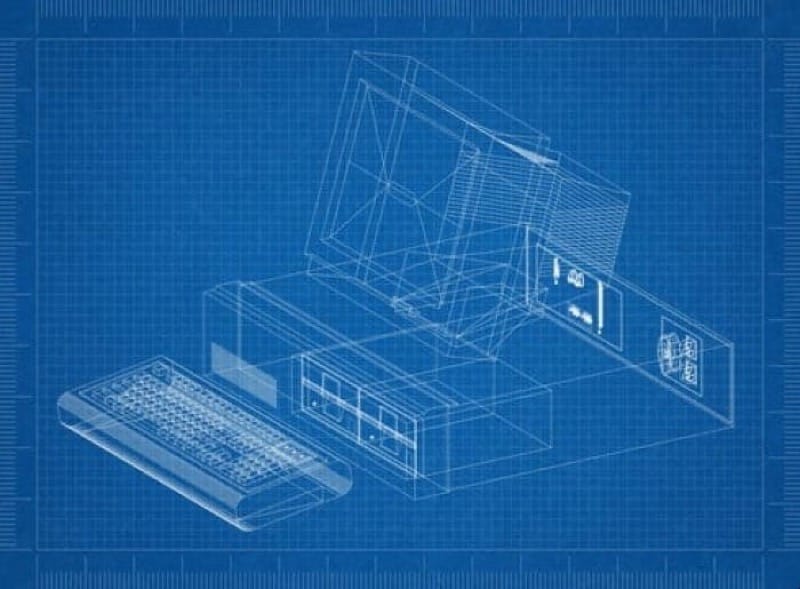

Open source is, by and large, software whose fundamental operating instructions – for humans and for the computer – are open and available to be modified and redistributed for use. That means people who didn't create the product, or who don't formally work on it, can see the code, perhaps even modify it, use it to build plugins or variations or other commercially viable products. For the purposes of this newsletter, let's think of anyone who engages with open source software in good faith as a member of a broader community. They're a supporter of open source software, or they also want to build cool stuff, or they want to contribute or participate in some way. They can do this because they have access to the source code, which is a blueprint – one that anyone can see and poke around in.

My friend Darius helpfully describes source code like this: "You can't fix your TV easily if you don't have a diagram that tells you how it's all wired up inside. But once you have that map of wires it becomes easier to tinker with. Source code is that map."

I like to think of it as a blueprint. A blueprint is a set of plans for something that works, but we don't have to copy the original exactly. We can modify it for our own needs or communities. The very blueprint of the software that runs the whole product is a blueprint any one of us could poke around in. It is not proprietary, and it is not hidden within a corporate fortress of ownership, protected by an extremely powerful legal army. We can use it, modify it, figure out how to make it work for us and our communities.

Why should you care? Well, a neat thing about open source is that you can't hide bad shit in it. By bad shit I mean stuff like, say, the part of the code that tells the app to take your data without your permission. You can't put something like that in open source software because someone will probably see it. But another neat thing, maybe the neatest, are two of the core principles of it all: Open collaboration and peer production.

Now, I am not about to suggest that open collaboration and peer production only happen in open source work, or that I am the first person to ever think about applying these principles to other aspects of product development or broader community building. I may be an asshole, but I am not that kind of asshole. These are hardly new concepts, whether in making economically viable apps or in doing grassroots organizing. People have been crowdsourcing since time immemorial!

But I am wondering this: Can we blend these models to create more alternatives to the structures we are caught in right now? Can we think about all the different things people do and don't understand, and find ways to translate into other languages and a better understanding for a wider range of people? Not just natural or computer languages, but visual or auditory, other modes of learning, modular pieces and steps to improving performance or experience, designs, even action networks or online community building?

A few weeks ago, I was on Bluesky – speaking of open source – and there was, as usual, something truly horrible happening in the United States. Also as usual, people were arguing. Someone was exhorting Americans to get up and do something. Someone else responded, "but what? what do I do?" The original exhorter's replied sincerely (hand to god): "Read these books. Books that help explain why all this :waves hands: is happening" and gave some titles.

Now, I love books. I love reading! I love learning and knowledge and information. I just don't think the person who felt helpless and hopeless wanted "read a book" as a suggestion of what to do. But a lot of people have that question. Give money, go to a protest, call a senator: These are all things people know, but might feel insufficient. You might say, "Leah, they're adults, they can figure it out. There are lots and lots of organizations out there with plenty of information or in need of volunteers, please stop reinventing the wheel." You would be right!

And yet. One thing I learned over and over again, working on all those proprietary software products, is something that won't surprise you: People are sheeple. A lot – like A LOT – of people look to others to know what to do, or to know whether what they're doing is ok, or to know that others are doing what they are about to do. This is why many people didn't share in Instagram Stories for the longest time: They had no idea what Stories were even for or whether they were sharing the right thing. So when most people stand around going, "I dunno what to do. Do you know?" and the best idea some guy can throw out is "read a book," what do we think is gonna happen? Not much! That's why so many people go out to a big march or protest and feel like, fuck yeah, we're all on the same wavelength.

So, again, what if we used open source models? What if we crowdsourced and grassrootsed some of this? If you know your history, you know about the Montgomery Bus Boycott. You know about Rosa Parks. You know the boycott lasted for a full year, and that it worked: Enough riders refused to use the city transit system that the system had to change. It wasn't economically feasible to do otherwise.

But the boycott didn't happen in a vacuum. People still had to live their lives and get around, go to work or school or the hospital. So the community had to come up with its own solutions: carpooling, taxis, cycling, walking, horse-drawn buggies, mules. Hitchhiking. Yes, even white housewives occasionally driving Black domestic servants. Each time the powers that be tried to squash an alternate form of transit. Each time, Black leaders, activists, and the Black community outmaneuvered them.

Because at the end of the day, we have a pretty simple choice to make: Inconvenience or injustice?

Please do not misunderstand me: I'm not comparing getting arrested on a bus in Jim Crow Alabama to something like quitting Substack and publishing on Ghost instead. I also acknowledge that a lot of what we can do isn't as visible (or relatively straightforward) as not taking the bus. We're surrounded by technology and institutions into which we have no visibility, over which we have no authority, that undergird most of our lives and control most of our media. But what if we stopped yelling at people to do something, and started giving them more blueprints of what to do and how to do it? What if we could create more alternatives, give people other options, help them understand how to make the best of those options, and try to put real economic pressure on some of these systems, since that's the only way they'll change? If Black people in Montgomery could spend all of 1956 not taking the bus and pushing back on Jim Crow, I'm pretty sure I can find a way to stop clicking on Instagram ads.

What if we were honest about the fact that tools like Substack sure are nice, with a ton of great features and a very, very active user base. Other options won't be as slick or have the same features or feelings, but as a community we want to help each other build more viable ways of sharing and connecting? What if we provided open source customer support, open source design, open source instructions and options and conversations about the technological choices people can make, and the tradeoffs they have to accept?

What if we remembered that building isn't just about making an app? It's about design, verbal communication, being willing to exist in spaces that aren't as immediately or constantly (artificially) vibrant. It's about doing the actual work of building and maintaining community, navigating conflict, dealing with difference, communicating and finding compromise.

Talking to computers is hard, but talking to humans is harder. What if we accepted that, and started there?

Until next Wednesday.

Lx

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.