Intelligence, Incentives, and Iron Men

Twenty-two years ago I submitted the thesis for my first graduate degree. This is the same thesis I mentioned back in February, the one I wrote when I still loved critical theory and when I still thought there was a place for me in academia. Neither that love nor that idealism survived the defense of that thesis or the eight subsequent years I spent pursuing my PhD in sociology. These were two signs I should have focused on a lot sooner as I cast about for a career path, but my thesis itself was maybe an even bigger sign. I still think a lot about what I wrote, not because it was a precocious work of genius – David Foster Wallace, I am not – but because even then I could see how our dysregulated intimacy with technology (and eventually with artificial intelligence) was going to end up.

Before I tell you about the thesis, I need to prepare everyone who didn't give in to temptation when I linked to it in that earlier newsletter. (Everyone who did give in to temptation, I'm sorry.) When I told you in that newsletter that I love a good theory, I mean I love it, and when I say now that I loved critical theory, I mean I loved it. Some years before I went back for my graduate degrees, maybe 1994 or 1995, I enrolled in an undergraduate seminar at Berkeley that was supposed to be taught by Avital Ronell. To be fair, she did teach some of it, although she disappeared midway through due to some unspecified personal emeregency, at which point a graduate student took over. This was apparently not uncommon for her, but it didn't matter because half a semester spent deconstructing Mary Shelly's Frankenstein was more than enough to blow my impressionable mind and change my thinking forever. A subsequent lecture by Judith Butler, who had only just joined the Berkeley Comp Lit faculty, introduced me to Donna Haraway. They were heady times!

I don't mean to discount literary or critical theory, or to mock anyone but myself. I was just very, very, very into all of it without the guidance of a supportive mentor. The advisor I attached myself to the first year of that graduate program went on sabbatical for my second year, and then I ended up in a PhD program that was hostile to critical theory, hostile being an understatement. There was a lot of potential in what I was doing but it lacked some discipline. (Story of my life.) So if you do skim the thesis, please keep all this in mind. Because even if my application of some theoretical texts was at times clumsy, the questions I was getting at were important then as now. I wrote about the representation of cyborgs and androids in popular culture, namely movies and literature because I wanted to know why we're so drawn to stories about artificial lifeforms that come back to control or destroy us after we create them. What are we trying to tell ourselves about this urge to play God? Are we hellbent on being complicit in our own destruction?

I was serious when I say that deconstructing Frankenstein did a number on me.

This week I read a beautiful and heartbreaking newsletter by Audrey Watters, one of those thoughtful, incisive pieces of writing that echo your own thoughts all while it makes you want to write better, do better, be better. It's one of the smartest pieces of writing I've seen on AI, in part because it is not about AI per se. It's not about the companies that make it, the CEOs who waste billions, and the specific perils of this or that software. It's about the vastly bigger picture – the inescapable origins of AI, computers, and the internet, and the forces that we would have to overcome to save ourselves from the inevitable sort of future these technologies seem to guide us toward. It isn't a very hopeful piece of writing but it is clear-eyed and honest about the seemingly insurmountable challenges we face, which is the sort of thing that gives me hope, strangely. No problem can truly be solved unless we understand it, all the way down to its darkest roots.

Whenever I tell people about the work I'm doing with my writing, how I want to find a way to carve out human-sized and shaped spaces online and in technology, and how hard that is, there's inevitably a moment when people say "well, that's because of capitalism." They're not wrong when they say this, just as they're not wrong about the influence of gender and race on every single technology that undergirds our lives. But this has always felt incomplete and unsatisfying to me, like we're missing another leviathan lurking in the depths, entirely to our own peril.

Then I had a conversation with a family friend last weekend. When I told him about the book I was hoping to write, and about this newsletter, he said, "How would you change the incentive structure?" He was focusing more on how I would measure success of a technology if I was going to argue away from growth, or how I would suggest creating an incentive structure for investments and compensation that could even conceive of competing with what the tech industry currently dangles as its carrot, which is basically the potential to become exceedingly wealthy.

But the word "incentive," along with Audrey Watters' newsletter, reminded me that yes, there is more at play and more at stake than capitalism, even if the economics are foundational and inescapable. Computing, as Watters points out, has its origins in late 19th Century industrialism and capitalism via workplace automation and scientific management (Taylorism mentioned again!), aka surveillance and control. And of course, the internet and the devices we use today exist in large part because of war, the military, and global power struggles. Which means that ultimately what undergirds all of it, including (especially?) AI, is power, domination, subjugation, control. Is there an incentive more powerful than power itself? If there is, we would have found it by now. Lord knows people have tried, and yet here we are, still creating and using technologies that will inevitably destroy us.

When I say us, I am intentionally making myself complicit in all this. One of the things I've forced myself to be aware of is the encroachment of AI and the erosion of my own resistance to it. It's easy to hate generative AI and ChatGPT and all the big tools you have to opt into, and it's equally easy to hate the AI generated news and search summaries foisted upon us at every turn. But for years now, we've been trained to focus on the first few search results at the top of the page. In fact, just as search results really degrading, causing people to dig deeper or modifying search terms by adding "Reddit" to try and get some sort of useful results, GenAI summaries appeared. So of course our natural inclination is to read whatever is at the top of the search results and click on the embedded links now provided by Google in the summarized text. I find myself doing this without realizing it, before I recognize the sleight of hand that keeps tricking me. I try to stop myself, because I don't want to boost metrics or train the LLM and the algorithms. I don't want the technology to train me. But even that imperceptible erosion makes me think of the countless other erosions that have happened and continue to happen everyday, the agency, memory, and power I keep giving up for smaller and smaller incentives.

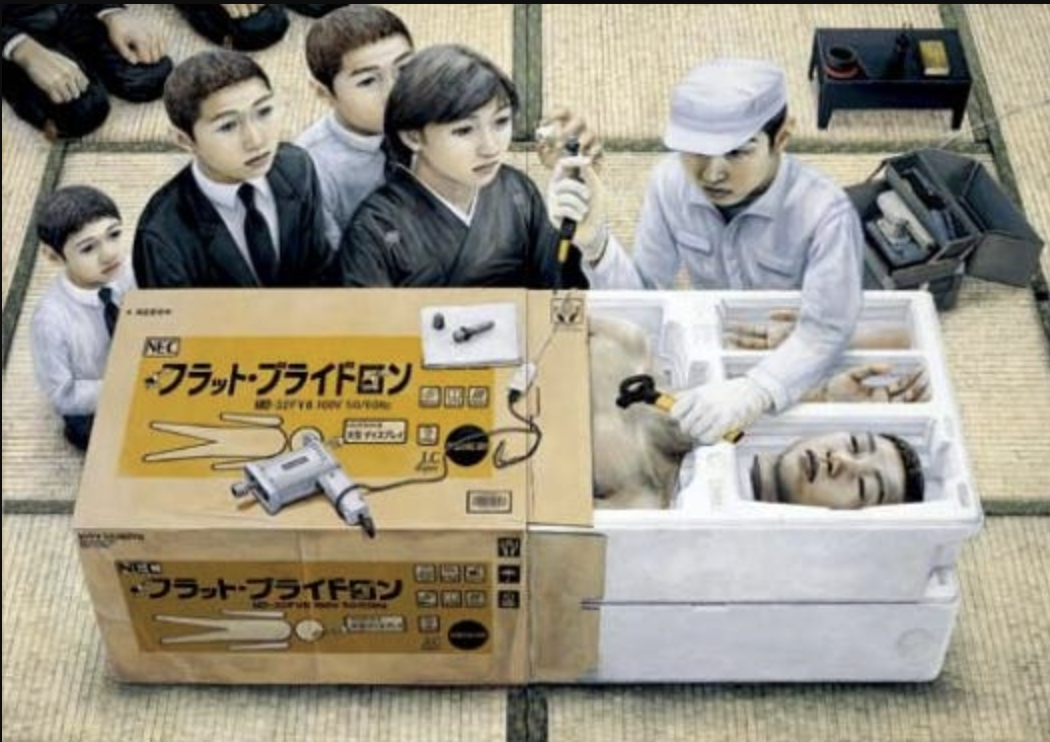

If you were in New York in the fall of 2023, you might have been lucky enough to see the Tetsuya Ishida exhibition "My Anxious Self" at Gagosian. Ishida was a young but hugely prolific painter who died in 2005 at age 32, leaving behind an extraordinary body of work, much of which he completed during Japan's 1990s recession, also known the "Lost Decade." I went to the show and was floored by the way he portrayed the despair and alienation that many people still feel in an increasingly automated and technologized world. It's the mirror image of the feeling I was so curious about when I wrote my thesis: Rather than focus on the cyborg that we want to build, he focuses on us, and the ways we are dismantled and reconfigured.

One of the movies I included in my thesis was a cult sci-fi horror Japanese film called Tetsuo: The Iron Man. It's a pretty subversive film, full of weird sexual fantasy-nightmares, about a salaryman who slowly transforms into a machine. I have to imagine Ishida saw this movie, or at least knew of it. Like his art, it's as much a warning for the future as it is a reflection of the era in which it was created. The incentive, all of this art seems to say, is pretty obvious: Create better technologies, better structures, better rewards, or lose everything that makes you human.

Until next Wednesday.

Lx

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.