Community Fetishism

A couple of months ago, I cancelled my New Yorker subscription. I was in the throes of feeling overwhelmed by what felt like a metastasizing list of subscriptions to streaming channels and publications and apps and services and newsletters. In order to see what I'd actually miss and consider adding back in to my media diet, I decided to shake things up a little. A sort of elimination diet, but for content. So I thought to myself: That subscription creating the ever-growing pile of unread magazines in my one-bedroom apartment seems like a good one to try out. After all, there it was, physical evidence of my bowl-of-oatmeal-like brain's inability to focus on 10,000 words about NATO when it could just refresh Reddit to skim yet another post analyzing a moment from Mad Men, or maybe an informative comment thread about brachiopods in r/FossilID.

But of course, even without a subscription, it's easy to keep up with whatever The New Yorker is up to. First of all, I live in New York in upper Manhattan so I think they put The New Yorker in the water, and second of all, I'm unfortunately online a lot. So I did see the piece Kyle Chayka wrote a few weeks ago called "It's Cool To Have No Followers Now." Even if I hadn't seen it, one of my friends would have sent it to me, because it's fun to remind me that this is who gets paid to write about tech when I essentially do not.

You know, Kyle is a nice guy, or was when I met him years ago, and I don't want to be mean for mean's sake. We no longer live in an era in which people regularly write things that would make modern online audiences have collective aneurysms. Like, for example, Renata Adler on Pauline Kael: "Line by line, and without interruption, worthless." Also these examples from the aforementioned spy book I'm reading also come to mind: "A purblind, disastrous megalomaniac” and “As an intelligence officer, he was inhibited by lack of imagination, inattention to detail, and sheer ignorance of the world." Or we could cede the floor to the true OGs of slinging verbal shit, Sir Thomas More and Martin Luther.

And let's be very real: I am no Lauren Oyler, nor am I an Andrea Long Chu. I know I do not have skin thick enough to take it when it inevitably gets dished out (please always be very nice and extremely complimentary to me, I am but a tender flower).

I do, however, want to make a habit of dealing critically with writing about tech and culture and people, particularly when it appears in a publication as august as The New Yorker. Especially when that writing, unfortunately, makes me feel like my "this is who gets to write about tech" ha ha funny joke is not funny at all.

The conceit of the piece, if you have not read it, is that we have stopped trusting large follower numbers on social media. More than that, we have decided that what is actually desirable and great is to have a small number of followers. It is bad to be overexposed, sexy to be secret. Bad to amass an audience, desirable to have devotees. You get the point. And look, maybe this is true. I don't know. I haven't done any research on it or read any research, and this is piece is not based on much besides vibes. So who's to say!

The problem isn't whether the argument is true or not, whether we've grown to mistrust big numbers and care more about small numbers. The problem is that the argument itself is specious. Not just specious but laughably superficial. Really? This is what passes for analysis in The New Yorker? You talked to some people you know? What do numbers even mean? What do they signify or reveal? What inherent value do or did they have? What made us start caring so much about these numbers? What value do we look for now? How do we define the relationship between someone who puts something into the world, and the people who choose to connect to and engage with that something? What's actually important here?

I remember when I was a sophomore in college and had a friend who lived in the freshman dorms with a roommate named Meg. This was 1993, and Meg was cool. Or at least she looked cool. Short pixie cut with outfits a mix of oversized pants and babydoll tops and big sweaters, the kind someone finds in a thrift store for $2 and then gets asked about every time she wears it. Everything was artfully mismatched but always mismatched in the right way so it still felt cohesive. It all seemed so effortless! So naturally cool! So completely Not Me. Then one day, my friend and I were walking to class and she says, "This morning, Meg spent an hour looking everywhere in our room for this one sweater that didn't match in the right way, that's why I was late, she made me wait for her."

Honestly, it blew my mind. I mean, I was 18 so this is kind of a low bar, but really! I understood then that there are two ways to directly engage with being cool: Either you try too hard to be cool or you try too hard to make it look like you're not trying too hard to be cool. Neither of them are cool, of course. Actual coolness comes from not even thinking about being cool at all.

So when I see all this about "respecting someone's sub-500 follower number" or how "it's a flex to post intentionally not good content," I think—well, sorry, but frankly I think it sounds like bullshit. There is nothing inherently special in a number. There is nothing cool about an intentional flex to signify something to people so they can feel in-the-know and better than some plebes. It's all the same as caring about big follower numbers and hyper-polished Instagram grids and the rest of it. You just care about the sweater not matching.

Do you know what is interesting though? Asking ourselves what we're looking for in these weird and frankly fucked-up digital spaces we've created. Asking ourselves why we started caring about numbers in the first place. Before around 2005 or so, the idea of followers and certainly the idea of tens of millions of followers, of going viral, of these massive network effects: A lot of that didn't even exist, and if it did, it was not yet the monster it would become. Examples existed, like in the form of blog readers and page views, or the Flickr explore page, or even MySpace. But what number did people really care about on MySpace? The Top Eight. Which implied exclusivity, the people who matter, the in-crowd. An early and major hint of the dopamine connection between numbers and value—specifically, emotional and social values.

Comparing a public account with a following of 12 million to a private, locked account with a following of 500 and saying that what's important is the difference in number is like comparing a Robert Altman movie with some made-by-AI Netflix series and thinking that the key element to consider is that one was made using film. Is film an element? Yes. But what does it imply? What does working with film mean? What else matters? I don't know, literally everything?

In my PhD program, I studied two very different methodologies. I trained to be an ethnographer, and I also learned social network analysis. These were two separate paths, and for many reasons I chose the former. I'm glad I learned ethnography, because it fundamentally changed how I see the world, but social network analysis was genuinely fascinating, and also the professor I worked with believed in me and was supportive, two things he did not share with my advisor, the ethnographer. We all unfortunately make dumb choices. So thank you, Dr. Butts, I should send you a long overdue email of gratitude.

Social network analysis, if you don't know, is (very roughly speaking) a method for analyzing social structures to understand the relationships between and amongst different nodes. These social structures can be all sorts of things, individuals or institutions, and the nodes that represent them are connected by edges or ties. If you have heard of the famous sociology paper "The Strength of Weak Ties," the ties are in part these literal lines linking one node to the next, and so on.

Let's say you're analyzing a network and you find a node. That node is connected by a million edges to a million other nodes. That sounds like a big deal, yeah? Big number! But all those little nodes connecting to the main node aren't connected to other nodes. They're isolates, or maybe connected to one or two others. Does this give the big node actual status?

Now you see another node in the network, which only has a thousand edges connecting it to other nodes. But the nodes on the other ends of those edges aren't singles or even dyad members. Those nodes have 10s, 100s, even 1000s of connections. The edges connecting those nodes are also different from the others. These are stronger: Quant data reveals a higher number of interactions, particularly reciprocal interactions, and qual data reveals that the majority of the edges are positive, based in shared interest or even friendship.

You go back to the other big node with the millions of edges and you realize most of those are unidirectional. There's no reciprocity. There's only one type of engagement, when it happens. Some nodes, like Kyle mentions, are there because they've forgotten to unfollow, others because they're hate following. So what actually matters here?

Right now, I'm going to do something that is uncomfortable for me, which is funny because I tend to be kind of an open book. Wanna know something? Ask me! I'll probably talk about it! But I'm going to tell you how many subscribers I have. When I look at my Ghost dashboard, I see that I have 1213 members. My subscriber number is under 1100, which I don't understand because the difference between member and subscriber isn't clear, but I guess some people don't have email subscription turned on for some reason. Anyway, the point is that this newsletter I send out faithfully every week has a dedicated readership of about 1200.

And honestly, it is dedicated! My average open rate is 70%. That's pretty good I think, especially considering how often I myself open emails in my own inbox. Sure I've had some people unsubscribe but that's normal, people come and go. I don't have a lot of commenting or activity on the newsletter itself, which I'd like to change (and encourage), in part because that requires people to click through and then login on a website. But yes: Roughly 1200 subscribers, 70% average open rate.

Why am I embarrassed? Why do I feel like that is an extremely lame number of people given the work I put into this thing? (More than you might think, despite outward appearances.) Why am I not proud that I've personally grown that number by at least 400 without all the built-in audience building tools of something like Substack? My readers don't have an app to go to where everything is served to them. They have to OPEN AN EMAIL, which again, to me, feels like the greatest compliment you can give. Why am I not merely delighted that 1200 of you have chosen to stick around, to open this thing, to read, to send me messages, to cheer me on, to share with others? I should be overjoyed that this many of you are not only here, you are reading. And I think I finally am, but not thanks to Kyle's piece.

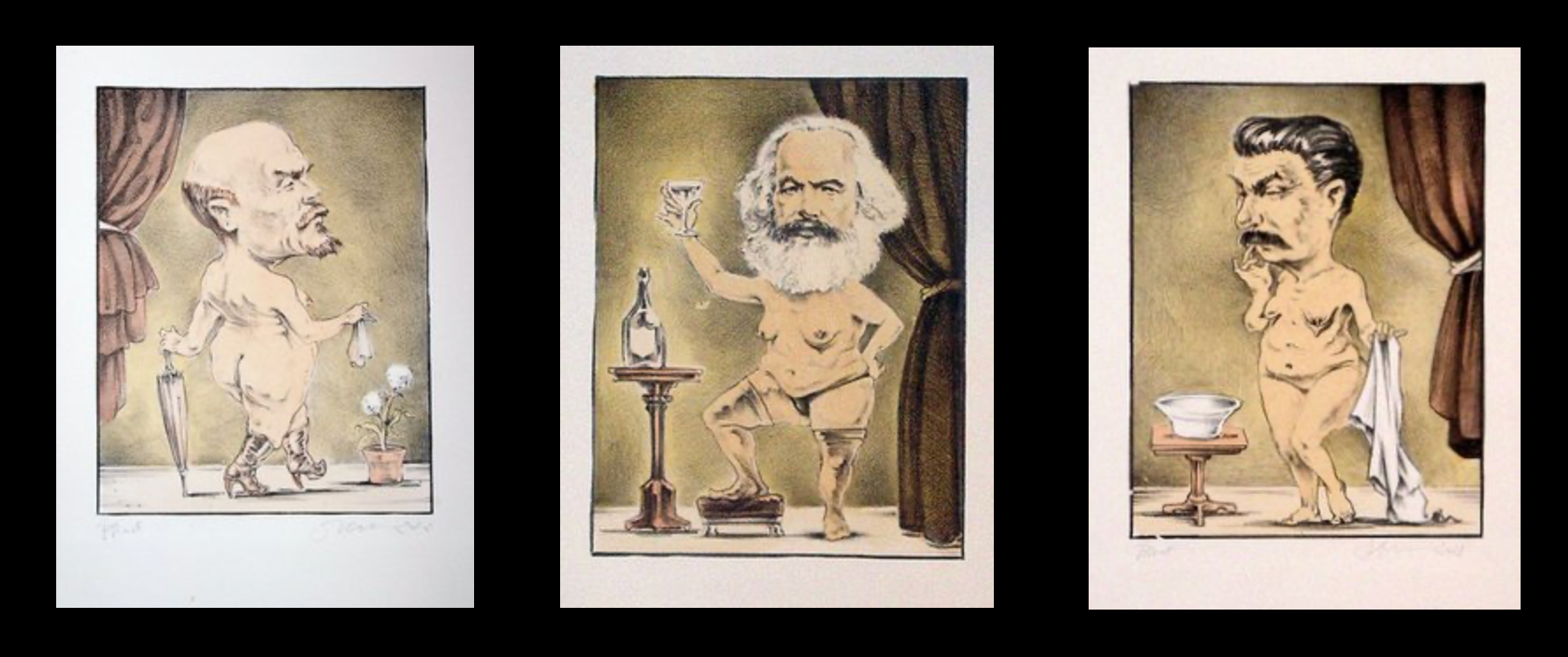

Well, no. I am, thanks to what Kyle's piece lacked, and what it made me think about. If you're familiar with our old friend Karl Marx, then you will undoubtedly know his work around commodity fetishism. Contrary to popular belief, this is not the fetishism we know as the (usually) sexual fixation on an object or a material good. Commodity fetishism is treating a material good as if it has magically appeared and thus has some inherent value that we can trade for money. It's seeing the object without seeing the labor and materials that went into making it, the relationships and the ways in which that labor and those materials are exploited.

This is what we are doing with numbers, especially follower numbers. We're treating them both as good and as the good. But unless you're:

- working with an advertiser who needs a certain number of eyes to see something in order for them to do an ad buy with you or promote your content, or

- a giant social media platform which relies on big accounts with lots of followers to drive the bulk of the traffic, and which also relies both on metrics and on inventory (and we all know what inventory is!) to show growth,

then who fucking cares about the follower numbers? In fact, who the fuck ever thought it was a good idea for one human being to have 12 million people connected to them in a way that enables them to send text messages, visual messages, even audio messages?

Again, I am going to say this over and over again: The idea of a public square for 300 million people is a BAD IDEA. What did anyone think was going to happen if 300 million people were able to share all their thoughts with others 24/7, all at the same time?

Anyway, back to Kyle Chayka and his rudimentary analysis, which of course is full of some of the cool people he talked to and the cool people he thinks you should follow but maybe not, because then they'll have big numbers.

Here's an idea: What if you care about what you are sharing and why? What if you care about who needs to see, hear, feel, understand what it is that you think is important to put into the world? What if you ask them to talk to you about these ideas or images, but in a way that's two humans should talk about these ideas or images: With reciprocity, with some level of respect, with savagery if it is earned, but not with two different sized bullhorns and a vast array of hateful, racist, antisemitic, homophobic, transphobic, misogynistic rhetoric?

What if you stop and realize that the main reason you care now about numbers is because a platform trained you to care about numbers. A platform that needs you to care about numbers. A platform that, like Substack, now shows everyone a little badge with numbers of how many paid subscriptions you have—as well as who you give money to—and then lets every newsletter writer know whether the commenter or person in the chat is a paid subscriber or not, with a handy little badge.

The numbers are a distraction, just like the commodity. What matters—and how many times am I gonna have to say it until everyone starts listening—is the people. The work. The material. Stop fetishizing the commodity, and build the community.

Until next Wednesday!

Lx

Leah Reich | Meets Most Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.